In its present state the United States Capitol exhibits four distinct architectural minds at work, those of its original designer, William Thornton; Benjamin Henry Latrobe, the architect responsible for erecting the major portion of the first building; Charles Bulfinch, responsible for redesigning and carrying out the central section including the rotunda; and Thomas U. Walter, the architect of the extensions and present dome. Montgomery Meigs of the Army Corps of Engineers worked closely with Walter on the structural aspects of the Capitol extensions and directed its elaborate decoration. As it would necessitate considerable backtracking to follow the Capitol's construction history, it is more practical to begin on the west terrace, comparing the exterior features of the original building with the later additions, before moving to the east, and then discussing the interiors.

The sole remaining exposed wall of the original Capitol consists of five bays to the north of the projecting west center wing completed by 1800 under George Hadfield (1795–1798) and James Hoban (1798–1800). The reciprocal bays on the south side were carried out by Latrobe between 1804 and 1807. These walls were built with brown Aquia, Virginia, sandstone, first painted white in 1818 and most recently restored in 1987 when eroded stones were replaced by Indiana limestone. The corresponding walls on the east front have been covered by the 32-foot-deep addition completed in 1962, when the original sandstone walls were replicated in Georgia marble.

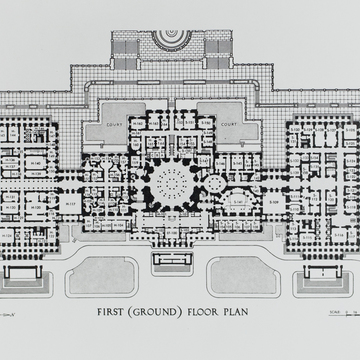

Office areas designed by Hugh Newell Jacobsen in 1991 fill the light courts between the original basement walls and the inside of the terraces. The basement walls are left exposed and are lit by skylights.

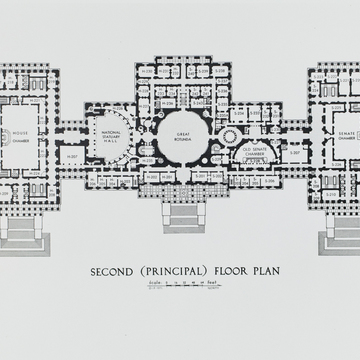

Thornton's design for the wall articulation was an elegant interpretation of a palace type, with a rusticated basement story, tall principal floor, and attic story. The compact original building has a balustrade masking the low roof, deep entablature, and guilloche frieze above the basement rustication. These horizontal lines are countered by the vertical organization of the windows into bays separated by two-story pilasters, producing a tightly woven abstract grid. In addition Thornton introduced numerous curvilinear elements into his composition, making the Capitol the first major building in the United States to be influenced by the eighteenth-century English Neoclassical style. Called the Federal style in America, it was characterized by horizontal massing, oval and circular rooms and wall elements, and delicate, attenuated proportions and details. In the center bay on each wing wall Thornton enclosed bull's-eye and arched windows within a shallow, semicircular arch to give a central focus to what was at the time in America a large expanse of wall. Segmental pediments over the principal floor windows continue the curved lines across the facade and were intended to be resolved visually in the center by two low saucer domes, one projecting to the west and the second

Despite its long building history, the exterior of the Capitol as a whole is in harmony, but there are differences between Thornton's facade and those adjoining by Bulfinch and Walter that reflect their differing interpretations of the classical tradition. For the projecting west wing Bulfinch made both major and minor changes to the pattern established by the earlier building. As Thornton's north and south wings had segmental pediments over the piano nobile windows, Bulfinch continued their use on the north and south faces of the west wing. Thornton probably had intended that the Capitol sit on a level plateau, rather than project over the brow of the hill. To increase office space Bulfinch added a sub-basement story on his west wing, erecting a terrace in 1826–1827 to mask it. These walls were visible from the terrace until 1991, when the courtyard between the terrace and basement walls began to be filled with offices designed by Hugh Newell Jacobsen. All of the east front basement walls will be left exposed and visible from a hall in the new interiors. Rather than employ quoins on the edges of his building, Thornton had used the more elegant double pilasters to terminate his composition. Bulfinch, apparently to strengthen the corner where the west projection meets the original walls, placed double pilasters on the inside angle but neglected to put them on the outside western edge of the walls. He did, however, use double pilasters on both ends of the portico face of his wing, so the articulation is correct when viewed from the front.

Walter continued all of the horizontal regulating lines of the original building in his 1851–1865 marble extensions. He preferred triangular pediments for all his facades. Careful comparison of the relationship between the walls and windows indicates some fundamental differences in sensibility between the Neoclassicism of the original building and the subsequent Renaissance Revival (a Victorian interpretation of classicism of a half century later). The spacing between the pilaster edges and window frames of the first building campaigns produced an even, measured rhythm across the walls. Walter closed the gap, introduced more windows, and created a much more rapid, staccato movement. In the Thornton-Bulfinch facades, the wall is treated as a neutral plane onto which pediments, brackets, and window frames have been attached; Walter's facades are activated with the sculptural elements treated more three dimensionally. They not only are denser but also project more from the wall and contain more elaborate detail. The crispness and intricacy of Walter's walls can best be seen by viewing their profiles against the sky.

The central section of the Capitol has undergone many design changes. Thornton planned a projecting, circular west front and a pedimented octastyle portico raised on an arcaded basement on the east. On the west he planned blank lateral walls between the wings and the small, circular center temple; on the east, single recessed bays that repeated the arched windows of his main walls to intervene between the wings and the portico. When the conference room was deleted from the building's program and the double dome abandoned, Latrobe designed octastyle porticoes for both fronts. His east portico stood in front of a colonnade spanning the width of the center section. It was reached by a monumental stair above a carriageway. Because its shallow pediment did not rise above the top of the entablature, views of his saucer dome were unimpaired. Bulfinch built Latrobe's design for the east portico, making the pediment higher to accommodate sculpture for which Latrobe had not planned.

Latrobe's projecting west portico was unpedimented and set within a wide wall flanked by single window bays. Bulfinch redesigned the west portico to project in front of a wall with a series of arcaded windows. Two sets of double columns flank two single columns, an unusual arrangement he had used earlier on the Massachusetts State House (1795–1797), probably known from a portico on Sir William Chambers's Somerset House (1776–1801) in London.

Bulfinch's dome, constructed in 1822–1824, had an unusually high profile to accommodate the request of James Madison and John Quincy Adams. Set above an octagonal stone drum, the inner hemispherical dome was largely of brick and stone while the outer dome was constructed of wood. It was sheathed in copper but never gilded. In 1851–1859 Walter planned a new focal point for the Capitol. He chose a cast-iron dome because it would be fireproof, lighter, cheaper, and more quickly erected than one in traditional masonry construction. In 1860–1861 the foundry Janes, Fowler, Kirtland and Company of Brooklyn delivered to the site 1.3 million pounds of cast and painted iron parts to be bolted together for a double dome held together by an extraordinary system of thirty-six continuous trussed ribs, apparently devised by Walter's chief draftsman August G. Schoenborn. On 2 December 1863 the final piece of Thomas Crawford's cast bronze statue, Freedom (19 feet 6 inches), cast in five parts by Clark Mills at his nearby foundry, was hoisted into position. Final weight of the ironwork was nearly 4,500 tons, the only dome of this size to be erected on an existing building.

Walter's design, with its four-part composition consisting of a thirty-six-column peristyle drum and intermediate attic, carrying the dome and tholos, traces its ancestry to Sir Christopher Wren's late seventeenth-century dome on Saint Paul's Cathedral in London. Auguste Ricard de Monferrand's cast-iron dome on Saint Isaac's Cathedral (1824–1858) in Saint Petersburg provided the most immediate model. The pyramidal composition of the Capitol dome—287 feet high, 135 feet in diameter at the base, and 88 feet at the cupola—resulted from structural necessity and aesthetic considerations. Even distribution of its weight on the rotunda and exterior foundation walls was of particular concern because of damage to the outside walls in the 1814 fire. A 14-foot iron ring was cantilevered out from Bulfinch's octagonal masonry drum and supported by seventy-two 15-foot brackets. Its iron skirt brought the base of the dome to the edge of the penultimate columns on the east front portico in an attempt to bring the new dome into visual harmony with both the original building and the new wings. Its size was calculated on the basis of the great length of the total building (751 feet) with its massiveness ameliorated by its openness. The skeletal cast-iron structure permitted vast expanses of glass on all four levels, flooding the interior with light, although only the drum windows are visible from the interior. Its sculptural three-dimensional quality in outline and in detail relates directly to the wings, drawing the whole into as much an integrated composition as possible given the disparate nature of the two architectural traditions represented.

Walter's wing extensions are attached to the main building by colonnaded hyphens, particularly successful in that they break the horizontal sweep of the Capitol into three manageable masses. Each rectangular wing was originally set perpendicular to and centered on the longitudinal axis of the main building, but the east front extension created an imbalance with the hyphen recess now deeper on the west than on the east. The honey-colored marble of the extensions came from Lee, Massachusetts. The infelicitous cold

Opinions as to which aspects of American history and ideology should be represented at the Capitol changed over time, as seen in the sculptural programs of the three east front pediments. President John Quincy Adams suggested the subject for the 81-foot 6-inch-wide central pediment, the Genius of America, the whole carved in sandstone by Italian-born sculptor Luigi Persico between 1825 and 1828. The originals were replaced by Georgia marble replicas when the east front was extended in 1958–1962. America, 9 feet tall, stands at the altar of liberty attended by Justice and Hope, classically garbed allegorical figures that harked back to the revolutionary era as its fiftieth anniversary was being celebrated.

A quarter century later the theme was manifest destiny, the belief that European-American dominance of the continent was preordained. Thomas Crawford's marble figures in the north wing pediment form a denser and more sophisticated composition and iconographical program, entitled the Progress of Civilization (1863). The central figure of America is flanked on the north by Indians and frontiersmen representing the early history of America. On the south a soldier, merchant, two youths, a schoolmaster instructing a child, and a mechanic illustrate the country's development as numerous professions contributed to civilizing it.

Marble sculpture for the south, or House, wing was not completed until 1916 and reflects the aesthetic and symbolic concerns of a well-established culture. Paul Bartlett's complex three-dimensional arrangement of attenuated figures represents two major aspects of American life. Entitled the Apotheosis of Democracy, the central composition depicts Peace protecting Genius; the figures on the north relate to agriculture and those on the south to industry. Each wing pediment is 80 feet long and 12 feet high at its apex. The exterior sculpture continues iconographic themes present much earlier on the interior.

Latrobe's three chambers, originally occupied by the Senate, House of Representatives, and the Supreme Court, and their subsidiary spaces, are the architectural glory of the Capitol. Constructed during two building campaigns (1803–1812 and 1815–1819), they were the most architecturally sophisticated spaces in America, carried out despite labor difficulties, lack of continuous and adequate congressional funding, shortages of material, and opposition to Latrobe's proposed changes to Thornton's original plan. Latrobe's detailed reports and exquisite drawings have made accurate twentieth-century restorations possible.

Although the interiors of the north wing were completed and occupied by Congress when Latrobe began work in 1803, their construction was faulty. In his rebuilding, Latrobe changed many elements but left the outlines of many major interior walls, which contributed to the criticism of the hallways as ill-lit mazes. In his interiors, Latrobe above all was conscious of making a building that was small, compared with contemporaneous European public buildings, appear monumental. He achieved this by creating layers of space within each room or visually connected area. The Supreme Court vestibule, which is entered through the Law Library door to the north of the central stair, is an excellent example of this practice. The small apsidal

The corncob columns were the first of three

Rooms serving major functions were not normally found on the ground story of classically inspired buildings. The Supreme Court chamber was probably located here due to space constraints in the original building, and this placement was viewed as a temporary expedient. It was the first of Latrobe's rooms to be completed that followed the same spatial arrangement. In the Supreme Court, space is not confined within visible walls nor does the actual physical weight of the vaults oppress. Space appears to be expanding in all directions, resulting in the appearance and reality of monumentality. Semicircular with a screen of columns along its diameter and angled piers around its circumference, the arrangement was based on ancient theater forms and had been revived in European eighteenth-century auditoriums. Faced with the problem of creating a room that had to support a two-story space above it yet reflect architecturally its important function, Latrobe visually and physically diminished the mass of the individual supporting elements. For his six Doric columns Latrobe used as a model early Greek columns with the exaggerated echinus that expresses in its bulge the great weight each carries. However, Latrobe's columns and piers are remarkably slender, contributing considerably to the sense of openness in the room. Formerly, natural light entered through the three large east windows, but the 1962 east front addition necessitated static backlighting at these windows, destroying the important interplay between form and space that changes as natural light shifts throughout the day. The layer of space behind the columns and piers functioned as small meeting areas yet were visually open to the main body of the room. In addition, the half dome is not a continuous surface, broken only by shallow coffers, but rather a series of butterfly vaults set between substantial ribs that spring from the polygonal piers. The language is classical but the principle of ribbed vaults is medieval. Latrobe's willingness to draw on numerous historical periods to solve structural and decorative problems at the Capitol resulted in unique spatial solutions. He achieved an eclectic mixture that was destined to become the hallmark of American architecture.

Adjacent to the Supreme Court is the two-story tobacco leaf rotunda set within oval walls that originally contained a major staircase of Thornton's design (destroyed by the fire of 1814). Latrobe's substitution of the rotunda with its own cupola brought light and air into the central circulation spine on both principal floors. The windows of the cupola have been closed and the rotunda is now lit by an inappropriate and vastly overscaled twentieth-century chandelier. The curved and arched piers on the ground floor obliterate the sense of being in an oval, a form that Latrobe disliked because of its geometric impurity and expensive construction. Yet Latrobe used the oval to create a subtle visual thread connecting the public circulation spaces on the ground floor. He cut the plan across its short axis and stood the resulting semicircle vertically within a semioval so that when one looks from the center of the tobacco-leaf rotunda through the crypt to the far hallway on the south, one sees a series of semicircular and semioval arches. Throughout the ground-floor halls, the walls are frequently articulated by open or blind semicircular openings set within half ovals.

The crypt was intended to function like ecclesiastical crypts, for it was hoped that Washington would be buried in a tomb below. The crisp profile of the entablatures and the general arrangement recall Sir Christopher Wren's crypt at Saint Paul's Cathedral. In addition, the center of the Capitol was the original prime meridian for the country (marked by the compass rose set in the floor). State lines were measured from this point, and the division of the city of Washington into its four quadrants was calculated from the center of the Capitol. In anticipation of large crowds visiting this space, Latrobe designed it (and Bulfinch executed it) to be as open and light-filled as possible. An outer double ring and inner single ring of slender, unfluted Doric columns carry elliptical vaults of an extraordinary lightness that are reminiscent of the vaults designed by Soane for

The present main staircase serving the south portion of the original building is an enlargement by Bulfinch of Latrobe's stair following the same constructional principles Latrobe had employed on the corresponding staircase on the north. Each marble tread is embedded in the wall and rests on the step below. Latrobe deviated from the standard practice of S-shaped steps, making his a quarter oval in profile, similar to stairs employed by the English Neoclassicist Robert Taylor. The scalloped outside edge of his steps particularly complements their curved form. The small octagon at the top of the stairs is Latrobe's oldest extant interior space in the House wing and the earliest surviving fragment of Greek Revival architecture in America; the Corinthian order is derived from the Tower of the Winds in Athens.

The present National Statuary Hall is the second chamber for the House of Representatives designed by Latrobe. The first, destroyed in 1814, was carried out between 1804 and 1807 in close collaboration with Thomas Jefferson as a double-apsed room, a compromise between the oval space of Thornton's plan, which Jefferson wished to build, and the semicircular room that Latrobe preferred. Latrobe's semicircular House chamber, built on the same semicircular plan as the earlier Supreme Court and Senate chambers, contained several inherent faults; these were due to the need to gain as much space as possible for an ever-expanding House membership by filling the rectangular envelope of the south wing. The acoustics were poor and it was difficult to heat. The curtains behind the columns replicate originals that only partially deadened echoes that plagued the room. Despite these problems, it is a beautiful room, but one marred by an inappropriate color scheme. To be historically correct and to harmonize better with the brown, gray, and white sandstone and marble structural elements, the turquoise should be light sky blue and the red a deeper burgundy; the curtains should also be darker.

The corner blocks contain staircases once open to the exterior and used by visitors to reach the second-story public gallery behind the columns. The gray shafts of the twenty Corinthian columns are Potomac Breccia marble; their elaborate capitals, based on those found on the Choragic Monument to Lysicrates in Athens, were carved in Italy of white Carrara marble at Jefferson's behest. The present cast-steel half-dome is decorated in clear, bold Greek Revival motifs in imitation of the original; it dates from 1901. Four white marble fireplaces are 1975 reproductions of the originals designed in 1812 by Giovanni Andrei and sculpted in Philadelphia by Adam Traquair. The originals had escaped destruction in the 1814 fire as they were in storage awaiting installation. In the center, putti, flanked by rings of thirteen stars, bind together the rods of the fasces. These symbols of authority and union are shown completed, carrying liberty caps, on the vertical supports of the mantles. Latrobe seems to have been the first to adopt these for an American symbol, although they had been common motifs during the French Revolution.

The north wing containing the old Senate chamber is the remaining part of the Capitol designed by Latrobe. He designed the tobacco leaf and flower order in 1816 for the sixteen columns of the rotunda outside the Senate chamber to replace a monumental double staircase damaged in 1814. The columns had to be more attenuated than Latrobe felt canons of classical taste allowed for in Ionic shafts, so he designed the tobacco leaf order to have “an intermediate effect approaching the character of the Corinthian order” 32 yet retaining a simplicity of outline agreeable to him. The capitals are now gilded and painted without any historical basis.

The inequality between the lengths of the east and west exterior walls of the north wing is resolved in the Senate vestibule, where the screen of Ionic columns masks the fact that the doors to the Senate to the east and offices to the west are not opposite one another. This vestibule, with its faceted corner piers and shallow dome carried on pendentives, is a little-remarked architectural gem of the building, a space where Latrobe proportioned and detailed each element with infinite care.

The Senate chamber as rebuilt after the 1814 fire retained its shape but was enlarged by about one quarter. The screen of gray Potomac Breccia columns with their Carrara marble Ionic capitals (modeled on those of the Erechtheum on the Athenian Acropolis)

As in the Supreme Court chamber directly below, natural light from east-facing windows was cut off by the 1958–1962 addition, and artificial lights were installed. The Senate's most unusual feature is the skylight, now covered and backlit. Light to the chamber was filtered through a series of translucent circular windows set within the curvature of the half dome. In this way Latrobe devised a compromise between cupolas with vertical windows, which often admit inadequate, diffuse light, and skylights, where glare, condensation, and heat are disadvantageous. It was probably Jefferson's insistence on a skylit roof for the original House chamber that stimulated Latrobe to contrive this solution.

The rotunda is Charles Bulfinch's major remaining public room at the Capitol. His Library of Congress, decorated with the order based on the Tower of the Winds in Athens, traversed the west center front. It burned in 1851, and Bulfinch's stairhall leading to it from the rotunda was redone by Carrère and Hastings in 1901. Latrobe's plan for an astylar rotunda included four large niches between the doors to house statues and stairs leading to the crypt below. John Trumbull's cycle of eight history paintings, commissioned by Congress in 1817, was to be placed between the niches and doors. When Bulfinch assumed office as architect of the Capitol in January 1818, many areas were incomplete.

Under Bulfinch the iconographic program of the Capitol was expanded to honor pre-Revolutionary events and people. Four of the eight horizontal decorative panels contain portraits by Francisco Jardella of early explorers who came to North America: John Cabot, Christopher Columbus, René de La Salle, and Sir Walter Raleigh. Sculptural panels of Aquia sandstone in the rotunda and figures for the niches on the east front codified the belief that European dominance of the American continent was inevitable and just. The earliest event recorded occurred in 1607, the Preservation of John Smith by Pocahontas, carved by Antonio Capellano and placed above the west door in 1825. Enrico Causici's representation of the 1620 Landing of the Pilgrims (east door) was completed in the same year. Nicholas Gevelot's William Penn's Treaty with the Indians (1682), above the north door, was done in 1827. Causici's 1826–1827 panel above the south door depicts Daniel Boone fighting the Indians. The two standing figures of War and Peace on the east portico are 1958 replicas of Luigi Persico's 1834 marble figures carved in Italy. The present marble relief of Fame and Peace Crowning George Washington over the east door is a reproduction done in 1959–1960 of Antonio Capellano's 1827 original. None of the European-born and -trained sculptors remained in America, ending their careers in France or Italy.

The dome above Bulfinch's sandstone frieze with wreaths is of cast iron, glass, and painted plaster. The handsome grisaille frieze recounting major events in the formation of America from the landing of Columbus to the California gold rush is 300 feet in circumference and 58 feet above the floor. Designed by Constantino Brumidi in 1859 but not begun until 1877, the frieze was unfinished at his death in 1880 but completed over the next eight years by a fellow Roman-trained artist, Filippo Costaggini. Probably due to a miscalculation, a 31-foot segment was left blank; in 1953 Allyn Cox added depictions of the Civil War, Spanish-American War, and the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk. The subject of the canopy painting executed by Brumidi is the Apotheosis of George Washington. It is suspended from the outer dome 180 feet above the rotunda floor and lit by windows not visible from below; until tours of the dome were limited, visitors could view the canopy painting from a balcony at its base, or from the gallery at the springing of the dome. Six groups of figures representing War, Science, Navigation, Commerce,

Although both Latrobe and Bulfinch worked within the Neoclassical tradition, their interpretations of the style differed considerably. Latrobe's penchant was for bold statements, and he freely mixed simple Greek orders, structurally articulated spaces derived from Roman architecture (perhaps directly or perhaps via English Neoclassical traditions), and medieval constructional principles to unify space and decoration. His creative spatial approach to architecture differed from Bulfinch's essentially decorative sensibility, which emphasized rich and elegant surface details. The decorative vocabulary Bulfinch employed was primarily Roman inspired. Areas of the building where he completed work begun by Latrobe suggest that he introduced decorative elements that were more delicate in scale and detail. In doing so, Bulfinch returned to the Federal style in which William Thornton had originally designed the Capitol.

The Capitol extensions contain some of the finest extant mid-Victorian interiors in America. Designed by Walter, Montgomery Meigs, and the Italian fresco painter hired by Meigs, Constantino Brumidi, they are characterized primarily by an exuberant explosion of color and pattern, making a more decisive break with the original building than do the extension's exteriors. The decorative vocabulary does not represent a unified vision but rather an eclectic mixture of Victorian versions of the Italian Renaissance style. Each wing is treated as a distinct composition, with the principal floor the most lavishly ornamented, following standard practice with Renaissance-derived buildings. Unfortunately, the present decoration of the current House and Senate chambers (done in 1949–1950 by Architect of the Capitol David Lynn) destroyed the two most important rooms, which combined brilliantly painted and gilded cast-iron decoration and an iron ceiling with inset glass panels evenly lighting the rectangular rooms. Numerous offices and committee rooms contain equally lavish interiors, albeit on a smaller scale, but there are few spaces open to the public where one can appreciate the true

The walls and vaulted ceilings of the Senate (north) wing ground-floor corridors are covered uniformly with fresco and oil paintings on plaster carried out by Brumidi and his assistants. The most interesting are the northern east-west and western north-south corridors where the decorative framework is composed of native American plants and animals mixed together with the traditional spiraling mixed together with the traditional spiraling acanthus leaves of Roman-derived decoration. The acid reds, greens, browns, and ochers used by Brumidi were substantially correct copies of ancient tones. Paintings of historic American events, symbols, and inventions as well as portraits of important figures are set within an ornate system of Roman-inspired frames, with some empty fields reserved to record future deeds. The barrel and groin vaults enhance the effect of an extensive and complex building enriched throughout in imitation of Roman and Renaissance architecture. The floors on all three levels in the Senate wing are covered with profusely patterned encaustic tiles in colors that harmonize with the walls. The commission to provide these tile floors for the Capitol was so large that the English manufacturer, the Minton Tile Company, later advertised that they were “tile makers to the US Capitol.”

Included in the spectacular architectural features of the extensions are the two marble imperial stairs for public use, adjacent to the east elevator vestibules in each wing. Lit by iron ceilings with glass etched and painted by the J. & G. H. Gibson Company of Philadelphia, these staircases are constructed of a richly veined, brown Tennessee marble. Unfluted columns on the second and third stories have black Corinthian capitals of cast bronze manufactured by Cornelius and Baker of Philadelphia. The coffered ceilings are of white Italian marble. The east front vestibules and their related staircases are among the few areas in the Capitol extensions where the color and opulence of the materials achieve a splendid effect without additional painting or gilding. The white marble of the vestibules is from Lee, Massachusetts, and the columns are one of Walter's two variants on the American order, where acanthus and tobacco leaves coexist harmoniously.

Both chambers are circumscribed by hallways open except for their entry vestibules and two members' staircases located at their outer corners. Designed by Brumidi in 1857, the newel posts and rails for the dogleg stairs were modeled by Edmond Baudin and cast in bronze by Archer, Warner, Minsky and Company of Philadelphia between 1857 and 1859. Stars, eagles, deer, and squirrels are incorporated into a three-dimensional design of children intertwined with a continuous acanthus arabesque, again combining Renaissance and American motifs in an exuberant and unified design.

The Senate Reception Room (S–213) is the only major remaining space on the principal floor where visitors can see the richest of the Victorian interpretations of Italian Renaissance interiors. Based upon Raphael's frescoed rooms at the Vatican (1508–1517), the walls and shallow domes are overlaid with modeled and gilded plaster. Frames for paintings and deeply undercut rosettes of an astonishing variety display the technical virtuosity of master plasterer Ernest Thomas. The extravagant use of uncommonly deep yellow gold from California in this room (and many others) celebrated America's resources, as did the numerous varieties of marbles and scagliola used throughout. The gold also reflects the meager natural light, as heavy curtains traditionally protected elaborately painted rooms to prevent fading. When the gas chandeliers were in use, their flickering light also reflected off the intricately carved gilded surfaces, enhancing the preciousness of the interiors. This luminosity, the shallow arches and domes, and the overall pattern of somber and rich colors create rooms of great intimacy.

The Hall of Columns on the first floor of the House wing is the most spectacular of the architectural features open to the public in the south extension. Twenty-eight stopped-fluted Corinthian-cum-American columns form a monumental entrance to the Capitol that extends from the south door through the entire 142-foot width of the wing. The white columns of Massachusetts marble have capitals designed by Walter as one of his American orders in which a single row of acanthus leaves is superimposed on one of tobacco leaves and thistles. The floors, originally laid in a colorful variety of encaustic tile designs, were replaced by the simple black and white marble pattern in 1924. The trabeated construction was made possible by castiron beams, and the combination of structural

There are four cast-bronze historiated doors at the Capitol, all modeled generically after Lorenzo Ghiberti's famous Gates of Paradise for the Baptistery in Florence. The most magnificent are the Columbus doors, since 1871 at the prominent east central door opening into the rotunda. Designed and modeled by Randolph Rogers in Rome in 1858, they were cast in Munich in 1861 and installed between the original hall of the House and the new south wing in 1863. Thomas Crawford designed doors for the main entrances to both extensions between 1855 and 1857. The Senate doors were cast in America and put in place in 1868, but those for the House were not cast until 1903 and installed two years later. Their rectangular and circular panels depict allegorical scenes and actual events of the Revolution. The doors designed by Louis Amateis in 1910 for the west center door were installed only in the east House stairwell south of the crypt. Their iconography is allegorical, with the apotheosis of America in the transom. Panels containing portraits of Americans represent various trades and professions.

Throughout the Capitol extensions one senses that the opulence of materials and Renaissance Revival designs were meant to express that the torch had passed from the Old World to the New, from the age considered the epitome of European civilization to the maturation of American ideals as its east and west coasts were united.

Notes

Latrobe to Thomas Jefferson, 5 November 1816, The Correspondence and Miscellaneous Papers of Benjamin Henry Latrobe, Vol. 3, 1811–1820 (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1988), pp. 622–23.