You are here

Susan Lawrence Dana House

Commissioned by an amenable client with a generous budget, at the propitious moment Frank Lloyd Wright commenced his Prairie Style work, the Susan Lawrence Dana House in Springfield is one of the most fully developed and well-preserved grand houses of Wright’s first mature period. In 1902, Wright’s architecture was rapidly evolving beyond the Louis Sullivan-influenced work of the 1890s. The power inherent in horizontality and clarity, glimpsed in Wright’s Winslow House (1893) and realized in the Willits House (1901), reasserts itself in the Dana House to produce an aesthetic expression intended to tie building and landscape together and to establish a regionalism that Wright believed was more evocative and meaningful than any revival style.

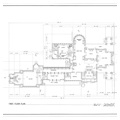

A social reformer herself, Susan Lawrence Dana was drawn to Wright’s reformist vision. When she commissioned Wright to remodel her father’s Italianate house for her own use, she was recovering from more than a decade of profound loss that included the death of her two infant children and her mining engineer husband, who was killed in an accident. Then, in 1901, her beloved father passed away, leaving Dana a significant fortune, which she increasingly devoted to political activism in support of suffrage and progressive causes—and to modern architecture. By the time Wright finished his renovation, little of the original house was intact, beyond the foundations and a single first-floor room. He had transformed the tightly bound box into a ranging 12,000-square-foot-structure with 35 rooms spreading out into the low prairie landscape, incorporating sculpture, art glass, furniture, flooring, and wall treatments.

Approaching the Dana House from the south, low, buff-colored Roman brick walls rise to a stone sill, with bands of art glass windows above, shadowed beneath a deeply overhanging decorative copper eave. The house rises to the second floor at the main entry, near the eastern end of the building. A curved art glass transom in an abstracted butterfly pattern surrounds the wide arched door. Ornate, green terra-cotta reliefs alternate with windows above the Roman brick base of the wall, with a low, red-tiled gabled roof above. Through the south entry, the visitor moves around Richard Bock’s sculpture, Flowers in a Crannied Wall, rising to the reception hall on the main entertaining level. Passing by the Bock-designed fountain, Moonchildren, one moves into the barrel-vaulted dining room. Abstracted sumac art glass chandeliers cast shadows upon delicate Japanese-inspired landscape murals, with sumac art glass windows lining the breakfast nook—the rounded apse at the end of the dining room. Wide porches and the long gallery wing spread the first floor of the house out into the landscape. Second-floor bedrooms are arranged compactly along a gallery open to the reception hall below, spatially connecting the first and second floors. In the Willits House and later Prairie Style houses, Wright frequently arranged the major spaces around a central fireplace to achieve compositional unity. At the expansive Dana House, he rotates those spaces around the multi-story reception hall.

With a virtually new mansion in Springfield’s most fashionable neighborhoods, Dana used her residence for entertaining the Springfield elite, and she was famous for hosting events ranging from political fundraisers to children’s Christmas parties. In time, however, Dana grew reclusive and her fortune diminished. After she was hospitalized in 1942, Dana’s personal property, including all her house furnishings, was put up for auction. The Wright-designed furniture, then considered unfashionable, found few buyers, and most items remained in place when Charles C. Thomas bought the house in 1944. Thomas operated his publishing company out of the house for nearly four decades. An admirer of Wright, he protected the house and its contents until 1981, when the State of Illinois purchased the property to operate it as a historic house museum. In 1990, the building reopened after a three-year renovation effort that returned the house to its historic condition and rehabilitated the rear coach house to serve as a visitor center.

References

Brooks, H. Allen. The Prairie School. New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Hitchcock, Henry-Russell. In the Nature of Materials: the Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright, 1887-1941.New York: Da Capo Press, 1942.

Secrest, Meryle. Frank Lloyd Wright; A Biography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

Sprague, Paul. Outdoors Illinoisv XII, NO8 (October 1973): 12-18.

Writing Credits

If SAH Archipedia has been useful to you, please consider supporting it.

SAH Archipedia tells the story of the United States through its buildings, landscapes, and cities. This freely available resource empowers the public with authoritative knowledge that deepens their understanding and appreciation of the built environment. But the Society of Architectural Historians, which created SAH Archipedia with University of Virginia Press, needs your support to maintain the high-caliber research, writing, photography, cartography, editing, design, and programming that make SAH Archipedia a trusted online resource available to all who value the history of place, heritage tourism, and learning.