Fontana Dam and Village are part of the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) system. On December 17, 1941, nine days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, Congress authorized construction of Fontana Dam on the Little Tennessee River in Graham County. The dam would support the war effort by providing electricity for the production of aluminum and for Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee. Named after a nearby settlement serving the Fontana Copper Company, construction of the dam began January 1, 1942 and was completed in November 1944, with the first turbine placed in operation January of the following year. This location was remote, sited sixty-five miles south of Knoxville on the southern border of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and the TVA built an entire infrastructure network to service the dam construction site, including a new community to house the workers.

Designed by TVA architect Roland A. Wank, this is the largest dam of the TVA system at 480 feet high, 2,365 feet long, and 376 feet thick at its base. The 11,000-acre reservoir, 1,500-square-mile drainage basin, and 240 miles of shoreline serves multiple purposes by producing electricity, providing flood control, aiding navigation, and creating new recreational amenities. It flooded dwellings, farms, towns, railroad lines, and other prior constructions in Graham and Swain counties.

Laborers worked round-the-clock shifts seven days a week to complete construction. Initially, tent camps provided worker housing in Gold Branch Cove, located three-quarters of a mile from the dam. This was a temporary measure until Fontana Village was built in Welch Cove, approximately 1.5 miles southwest of the dam. The community housed some 3,826 workers and their families. The Village included trailers, trailer houses, demountable houses, temporary houses, dormitories, and permanent houses built by the TVA, and 176 parking spots for privately owned trailers. Municipal infrastructure, two schools, and community facilities completed the village.

Fontana Village is among the first communities of prefabricated dwellings in the country, employing a modern construction process accentuated with a notably modernist aesthetic. Unlike earlier community planning projects and residential architecture sponsored by the TVA, there was little need for the rustic “vernacular” to soften the “future shock” of modern living because, as the historian Walter Creese notes, “that blow had already landed.” Fontana was also different because it lacked the suburban model of community planning: the idea of single lots surrounded by a lawn and fences was abolished, ornamental landscaping was absent, and dwellings were organized along informal roads adapted to the varied topography of the Smoky Mountains.

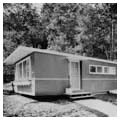

Of all the various house types at Fontana, most famous are the 104 trailer houses that were completely built offsite in a factory and delivered in two halves. The 7.75 x 24 x 8–foot halves were made of stressed-skin plywood construction with linoleum floors and sliding windows. They arrived painted, with electricity and plumbing installed; they featured built-in cabinets, moveable and built-in furniture, gas stoves, and an oil heating system. Once delivered on site, the two halves were rolled onto wood-post foundations and bolted together, the roof was then capped with wooden cover tiles, and the front steps and door canopy built. At the time, prefabrication was a symbol of modernity, the industrialization of the building profession was at its zenith, and the simple finishing in these trailers provided the clean lines and efficiency central to modern residential architecture. Efficiency of material and construction was not purely for stylistic reasons—it was imperative during the war effort.

One hundred demountable houses were also transferred to Fontana from the Hiwassee project. These houses were based on a 7.5 x 22–foot “cell,” supported by wood post foundations on wood blocks. Sixty-eight two-cell, one-bedroom units and 34 four-cell, three-bedroom units were brought to the site. Each had a small bathroom, kitchenette recess with electric range and icebox, electric water heater, and oil space heater. Daylight flooded living spaces through large windows; automatic plumbing, heating, and cooking provided labor-saving strategies for domestic work; and large decks extended limited interior space.

Twenty-five permanent houses for management and TVA officials were almost entirely located along Fontana Road, which led from the village to the dam. They were built with cinderblock foundations on concrete footings. The exterior walls were covered with asbestos-cement board siding and the roofs with asbestos-cement shingles. The houses had wood casement windows, full kitchens, and electric heat supplemented by a fireplace. Additionally, there were 155 temporary houses, including 93 duplexes also built of conventional frame construction but resting instead on creosote wood posts and footings. These houses had painted shiplap siding, asphalt shingle roofs, and double-hung sash windows. Materials were precut in the factory and assembled on site.

Once the dam was complete only a small contingent of workers needed to stay on for maintenance operations, so 32 temporary houses were renovated and remained in use, along with the 25 permanent houses for TVA officials. Many other buildings were sold, including the pool hall, recreation building, and some of the dormitories; others were disassembled and transported to various TVA projects along with some of trailer houses. Many trailers were sold to private individuals who hauled them away for use as permanent residences or vacation houses, but countless more remained on site.

TVA officials needed a use for the considerable outlay of community infrastructure and services at Fontana Village. When the military proved uninterested in its use as a retreat facility, Government Services, Inc., a nonprofit distributing company, signed a 30-year lease to develop it as a resort community in hopes of benefitting from the recently established Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The town incorporated in 2011 and remains a vacation resort.

References

Bishir, Catherine W., Michael T. Southern and Jennifer F. Martin. A Guide to the Historic Architecture of Western North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Creese, Walter L. TVA’s Public Planning: The Vision, The Reality. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1990.

“Factory-Built Houses of TVA Sectional Design Provide Thousands of War Homes.” Construction Methods26 (September, 1944): 66-69.

Morris, Suzanne K. “Housing Looks Ahead.” Science Illustrated(November, 1944): 4-17.

“The Miracle in the Wilderness.” Tennessee Valley Authority. Accessed March 11, 2019. https://www.tva.com/.

Madden, Bridget. “Notes on the Built Environment: Fontana Village.” North Carolina Miscellany, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Accessed March 11, 2019. https://blogs.lib.unc.edu/.

Moffett, Marian and Lawrence Wodehouse. Built for the People of the United States: Fifty Years of TVA Architecture. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1983.

United States Tennessee Valley Authority. The Fontana Project: A Comprehensive Report on the Planning, Design, Construction, and Initial Operations of the Fontana Project. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1950.

“Trailer House, TVA’s New Approach to Mobile Shelter.” Architectural Record93 (February 1943): 49-52

“TVA ‘Sectional’ Houses Now Include Two and Three Bedroom Models Made up From as Many as Six Truckable Units.” Architectural Record80 (March, 1944): 75-78

Woodbury, Clarence. “Resort That War Built.” Holiday1 (August, 1946): 36-38