School No. 8 was architect Louise Bethune’s first school project. It set an important precedent for public school design and also helped to establish her groundbreaking career. Commissioned in 1883, the three-story public school was completed at the substantial cost of $50,000 the following year. Supported by the Buffalo City Schools Superintendent James Crooker, Bethune’s firm designed the school according to a set of principles that were not fully articulated by other architects until a decade after it was built. Bethune’s design anticipated and embraced emerging concerns for student and teacher health, safety, and efficiency, which later became the standard by the early twentieth century.

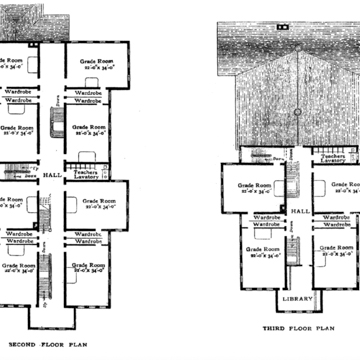

The school’s traditional exterior contrasted with the technological and organizational innovations inside. The building accommodated 1,000 students, with a cruciform massing reminiscent of cathedrals. Stylistic accents such as a steeple, clock, and Romanesque windows emphasized the medieval reference. Inside, there were twenty classrooms of equal size and fifteen-foot-high ceilings. The arrangement of the building assisted in separating different age groups, divided by floor with the youngest at the ground floor and the ages ascending with each floor. Separating students into groups, by floor and by room, it was increasingly believed, would enhance their ability to learn. There were also separate classrooms for each teacher, considered an innovation at the time, with teacher lavatories on each floor and student coatrooms adjacent to each classroom.

Many aspects of the school’s interior plan reflected Bethune’s understanding of cutting-edge research on the relationship between school architecture and student health and safety. New architectural approaches began to reflect concerns for proper ventilation, heating, lighting, fireproofing, and circulation. The “scientific improvement” of schools and student education could be better addressed, many believed, through standardized school design. Proper room sizes, specific distances to the window, and placement of the teacher’s podium could directly influence the physical health and safety of teachers and students alike. Many of the new, precise standards aimed to enhance air circulation by means of tall ceilings and window placement, and to improve light quality, in terms of the preferred direction of light falling over a student’s left shoulder. Much of this research was being conducted contemporaneously with Bethune’s design, but architects did not reach a general consensus about acceptable standards in publications until the 1890s–1900s.

School No. 8’s interior plan was consistent with the latest research on the physical environment in German schools, reflecting the shift away from the English and French single-room assembly method to the individual grade-level classrooms favored in Germany. Room proportions, orientation, and window spacing were sized and arranged according to this research, which attempted to scientifically improve education through an optimal set of specific measurements. Fire safety was addressed in terms of building materials, with two layers of hardwood floors separated by mortar to prevent spreading, as well as through the building’s layout. Multiple wide staircases were included for circulation, and two exits were located at opposite ends of each classroom. This allowed for quick exits in the form of new fire drills that proved 1,000 students could exit the building within two minutes. The school also incorporated innovative approaches to sanitation, steam heating, and sewer gas ventilation, attempting to minimize disease through architectural design.

Superintendent Crooker was thrilled with Bethune’s design for School No. 8, calling it “as perfect as ingenuity and the practical application of hygienic science can make it.” Bethune designed seventeen more schools in Western New York, most of which have been demolished or subsumed inside subsequent additions or alterations. Despite fireproofing efforts, School No. 8 was destroyed by fire in 1918, and a new school building was erected according to modern principles on its site. Regardless, School No. 8 represented a pivotal moment in Bethune’s career and in the history of school design in New York State. As Bethune biographer Johanna Hays has reflected, “Bethune not only designed schools, she thought them through from scratch, reinventing what they should be.” The results of that reinvention can be seen across New York State today, in the presence of many subsequent schools that followed the same standards around the turn of the twentieth century.

References

American School Board Journal. New York: William George Bruce, 1902.

Crooker, James F. Department of Education Report: Superintendent of Education, City of Buffalo, 1883–1884. Buffalo, NY: Laughlin and Company, 1885.

Department of Public Works. “School No. 8, Utica Street School,” Buffalo: B&ECPL Digital Collections. Accessed October 30, 2021. http://digital.buffalolib.org/document/1760.

Hays, Johanna. Louise Blanchard Bethune: America’s First Female Professional Architect. Jefferson, NC: McFarland and Company, 2014.

Proceedings of the First, Second and Third Congresses of the American School Hygiene Association. Springfield, IL: American School Hygiene Association, 1910.

Shaw, Edward Richard. School Hygiene. London: MacMillan and Company, 1901.

The Sanitary Engineer 8 (August 30, 1883): 307.

Warren, Suzanne. “Context Study: The Schools of New York State.” Ithaca, New York: Cornell University, August 1990.

Weed, G. Morton. School Days of Yesterday: The Story of the Buffalo Public Schools. Buffalo, NY: Buffalo Board of Education, 2001.

Wheelwright, Edmund March. School Architecture. Boston: Rogers and Manson, 1901.