Along with Trinity Church in Boston, this complex must be accounted as the masterpiece of Richardson's standing works; it is also the second most frequently imitated building in the United States after Independence Hall. The building was pivotal for Pittsburgh. Before the courthouse, Pittsburgh had not a single monumental building, nor did it have a proper downtown, since its main streets were given over to industry. With the construction of the courthouse, everything changed. Grant Street was edged with palatial skyscrapers, industry cleared out of the downtown, and Pittsburgh's citizens had, at last, a model of great architecture on a grand scale that private patrons like Carnegie, Frick, Heinz, and Westinghouse could emulate when they considered designs for their offices, factories, and charitable benefactions. Judge Thomas Mellon was alone in protesting the extravagance of the new courthouse.

After the Greek Revival Courthouse—a decent but provincial building—burned in 1882, the Allegheny County commissioners planned for the most modern of government buildings. They selected their architect with equal care. The short list included two prominent westerners (William W. Boyington of

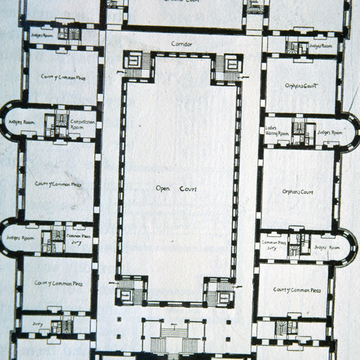

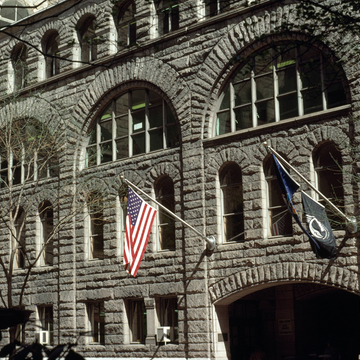

Richardson took the lead from the first, with elaborate photolithographs showing the proposed building in the smoky setting of downtown Pittsburgh. The design appropriated medieval sources on the outside: Salamanca Cathedral's detailing for the front tower; Venice's campanile for those at the rear; cornice from Notre-Dame in Paris; the Bridge of Sighs from Venice; basic hollow-rectangle massing from the Palazzo Farnese in Rome; and the four miniature towers a copy of his own work for Sever Hall at Harvard University. Inside, the building showed the best of the early Beaux-Arts methodology of French architects J.-N.-L. Durand and Henri Labrouste: superb circulation; inventive and economical use of space; natural illumination flooding in from the courtyard and the street; maximum efficiency for judges, juries, lawyers, and police; and even decent accommodation for the accused. The “newer” Beaux-Arts thinking was present as well, evident in the dramatic main staircase that recalls the one at Charles Garnier's Opera in Paris, and in the courtrooms that originally were of operatic sumptuousness. Courtroom 321 was stunningly restored by UDA Architects in 1987, spurred on by architectural historian Lu Donnelly and financed by the lawyers of Allegheny County. The jail was converted to courtrooms and offices for the county's family courts by IKM Architects in 2000.

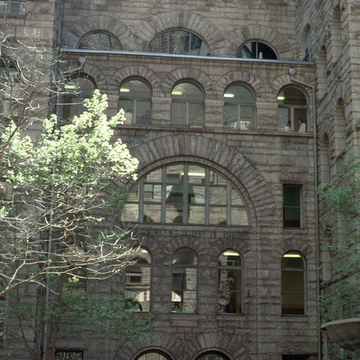

Richardson's strength as a designer is also evident in the courtyard. Here he dropped all allusion to history and worked in the pure rhythmic abstraction of his walls of Massachusetts granite. It was perhaps the first design for a public building in the nation that did not draw from any one specific historical source. When this courtyard facade design was turned to street facade for his Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1885–1887) in Chicago, it had an impact on American design for decades.

Richardson also considered the relationship between the courthouse and jail with Pittsburgh's downtown. The front tower acts like a compass, with the sun lighting up first its east face (toward the Hill and Oakland), then its south face (toward South Side), and, finally, its west face (Grant Street, but darkened now by the Frick Building), as though it were a sort of civic cathedral for the citizenry. The configuration of the long sides, with their brooding arches flanked by tiny towers, almost surely comes from Roman city gates: to enter the Courthouse is to enter the city in microcosm.

Though critical reaction has always fixated on the more dramatic jail, which now houses supplementary courtrooms, it is in the courthouse that one sees best Richardson's genius for providing not only the required functions but also fulfilling the client's longing for an image.