In 1796, the year Tennessee entered the Union, George Washington’s cousin Joseph moved from Virginia to secure a land grant for sixty acres along the north side of Sulphur Creek. He purchased an adjacent 640 acres between Sulphur Creek and Calebs Creek, about three-and-a-half miles south of what is now Cedar Hill, Tennessee, in 1802. Washington also began to purchase slaves to cultivate corn, fruit trees, and, most profitable of all, tobacco. At the age of 42, he acquired more acreage with his 1808 marriage to 16-year-old Mary Cheatham, daughter of one of the most prominent families in Middle Tennessee.

Log cabins, no longer extant, served as the first quarters for Washington’s family and for his slaves. By 1815, work began on the existing brick main house, built in the Federal style. Finished in 1819, the structure was built from bricks the slaves made on site. Two stories high, the original house was arranged around a central hall, with one large room to either side and a one-room ell to the rear. The house was named “Wessyngton” after the ancient Norman version of “Washington.”

By 1860, under the management of Joseph and Mary’s son, George A. Washington, Wessyngton grew to over 13,000 acres worked by 274 slaves who were housed in forty log cabins. According to historian John F. Baker, Wessyngton was the largest tobacco plantation in the country and the second largest in the world. In contrast, the Hermitage , Andrew Jackson’s plantation near Nashville, never exceeded 1,050 acres and was never worked by more than 150 slaves at one time. Besides tobacco, Wessyngton was also famous for its high-quality hams, which were marketed as “Washington Hams” and served in fine hotels from New Orleans to Philadelphia.

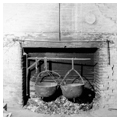

During the mid-nineteenth century, a wing was added on the west side of Wessyngton, and, on the south side, a large kitchen and laundry facility. The house eventually took on a U-shape, forming an irregular courtyard to the rear. Around 1905, the front, rear, and side porches were fitted with shallow mansard roofs, giving the Federal mansion a Second Empire touch. A Victorian gazebo, still extant, lies 100 feet from the east end of the house.

Because of the many additions and alterations over the years, the house is no longer a pristine example of early-nineteenth-century architecture. The importance of the property lies in its economic significance, its association with the Washington family, and as the home for generations of enslaved persons and their descendants. With rare exceptions, the Washington family never sold its slaves, preferring instead to house and work them one generation after the next. After emancipation in 1865, many of Washington’s former slaves stayed on as tenant farmers.

Though there was some discussion in the early 1970s of purchasing the property for use as a public museum and park, Wessyngton remains in private hands, still owned by the descendants of Joseph Washington.

References

Baker, John F. The Washingtons of Wessyngton Plantation. New York: Atria Books, 2008.

Eberling, May Dean, “Wessyngton,” Robertson County, Tennessee. National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form, 1971. National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

West, Carroll Van. “Wessyngton Plantation.” In Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Tennessee Historical Society, 2002–2016. Last updated January 1, 2010. www.tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entry.php?rec=1490.