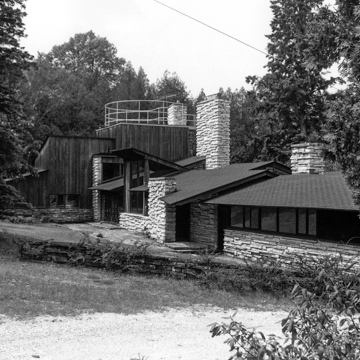

With this house, Keck embraced the principles of Organicism, articulated by Frank Lloyd Wright and others. Nestled into a hillside on a wooded site overlooking Green Bay—a location chosen by landscape architect Jens Jensen—the building seems an intrinsic part of its setting, a character enhanced by its materials. Long slabs of Door County limestone lie in horizontal courses, randomly projecting from the walls to mimic naturally eroded outcrops. The horizontal slabs contrast with vertical wall planks, made of fir to blend with the surrounding woods. Keck further tied the house to nature by using glass walls and clerestories to offer views of the sky, changing weather formations, and the northern lights. Limestone floors flow out of living spaces to form outdoor terraces, and limestone walls continue through the windows into the house. By juxtaposing squares, rectangles, and trapezoids, Keck moved away from the boxy geometry of his earlier designs. These lend the house a rambling, additive appearance.

While the geometric and organic vocabulary suggested a new direction in Keck’s work, the passive solar design reflected an interest he had been pursuing at least since 1933 when he unveiled his House of Tomorrow at the Century of Progress exhibition in Chicago. He thereby placed himself at the forefront of passive solar architecture in the United States. In the Buchbinder House, he combined glass walls and clerestories with shed roofs of varying heights to capture sunlight at all times of the year. But Buchbinder complained that the abundant sunlight made the principal rooms unlivable during the daytime. He resolved the problem with window coverings.