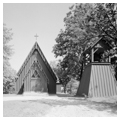

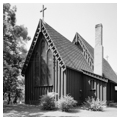

St. John Chrysostom Church is an exceptional example of Carpenter Gothic religious architecture. A steeply pitched gabled roof shelters the rectangular nave of this board-and-batten church. The slightly smaller but equally steep gable on the east end covers the chancel. There, delicate bargeboards, pierced with quatrefoil and diamond-tracery motifs, trim both gables, and a triple lancet of stained glass lights the interior. The board-and-batten entrance vestibule on the west side dates from the 1950s. The unusual freestanding board-and-batten bell tower is original; a small gable shelters its open belfry. St. John’s interior is crafted almost entirely of wood. A beamed ceiling covers the nave and its wooden pews, and an oak Gothic-arched rood screen, which carpenter Kelly embellished with trefoil tracery, separates the nave from the chancel. Local blacksmith Jacob Luther contributed the hand-wrought iron hinges, meant to evoke the branches of a tree, symbol of the resurrection.

St. John strongly resembles a country church design that renowned church architect Richard Upjohn published in his 1852 pattern book, Upjohn’s Rural Architecture. St. John’s nave and chancel are nearly the same size and proportion as the pattern book prototype. So is the exterior, except that St. John lacks a steeple. The woodwork inside—pulpit, lectern, and baptismal font—also echoes Upjohn’s design. Consequently, some scholars have attributed the design of this building to Upjohn. But construction of this church began a full year before Upjohn published his book. Moreover, none of Upjohn’s wooden churches had tracery in their bargeboards—the detail that makes St. John Chrysostom distinctive. Church history attributes St. John’s design to Ralston Cox, the brother-in-law of the church’s missionary, the Reverend William Markoe. Cox probably based his design on Upjohn’s work, either a church he had seen or one of the plans Upjohn produced for another rural congregation.