With the decline of wheat production in the late nineteenth century, farmers in sandy-soiled central Wisconsin began growing potatoes as a cash crop. Waushara, Waupaca, and Portage counties experienced phenomenal growth as potato-producing areas after 1870, and by 1900 potatoes ranked as the state’s leading cash crop. But potato farmers in northern Waushara County had to haul their produce to Plainfield, some twelve miles to the northwest. That changed in 1901, when the Chicago and North Western Railway reached the hamlet of Wild Rose, positioning it to become a major shipping point for area farmers. The coming of the railroad ushered in as big a boom as this small town has ever seen, as farmers brought wagonloads of potatoes to be sorted, graded, stored, and shipped.

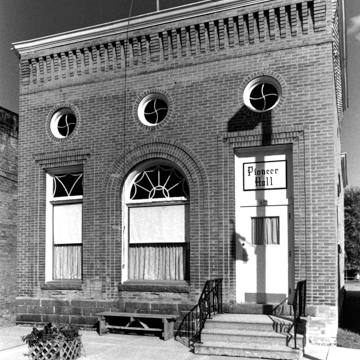

To provide financial service to this new market, local businessmen organized the Wild Rose State Bank, now a museum. The one-story brick bank is charming. It suggests no particular style, yet it is singularly stylish. At the center of the facade is a round-arched window, its fanlight rendered in a wispy spiderweb pattern. Rectangular openings flank the arch: to one side, a tall window features an elegant scallop-and-triangle motif in its transom, which echoes the pattern in the fanlight, and on the other side is the entrance. Above the first level is an eye-catching trio of ocular windows, their muntins arranged in a pinwheel pattern. A tall corbel table is below the cornice, and a triple row of bricks outlines the windows and doors.