After World War II, industrial design and architecture became increasingly intertwined, especially when large manufacturers, like International Business Machines (IBM), consulted with teams of designers to advance the company’s product lines and to shape the company’s buildings. In the post-war period, companies like IBM came to regard these facilities, whether they were dedicated to research, production, or administration, as part of their branded image, and almost as representative of the company as the products it made. And like those products, the buildings were required to incorporate the latest materials and technologies to prove that the company was on the cutting edge of innovation.

In 1956, IBM president Thomas Watson Jr. hired Eliot F. Noyes as “Consultant Director of Design” and charged him with entirely reinventing IBM’s corporate image. An industrial designer and architect, Noyes was a graduate of Harvard University (1938) whose influential mentor, Walter Gropius, had exposed him to the philosophy of the German Werkbund, which viewed good design as good business. In Watson, Noyes found an employer with the same commitment to design. To raise IBM’s design profile, Noyes assembled a team of significant modernists, including Charles Eames, Paul Rand, Edgar Kaufmann Jr., Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, Paul Rudolph, and Eero Saarinen, who worked independently and in collaboration with IBM’s in-house designers and engineers to bring Noyes’s aesthetic and technological vision of modernism into American life.

Soon after Noyes joined IBM, the company turned its attention to developing new manufacturing, engineering, and educational facilities on a 397-acre site outside of Rochester, Minnesota. This site was chosen to manufacture IBM electric and electronic accounting machines and to develop new products for punch-card tabulating machines and the IBM 305 RAMAC disk drive. Eero Saarinen was selected to design the corporate campus, which he proposed as a series of building blocks surrounding courtyards, some interior and some exterior, on a module that allowed for future expansion on the site. This was a design strategy developed by Noyes that had been recently used on corporate campuses for Time Inc. and IBM’s New York locations at Yorktown Heights and Poughkeepsie.

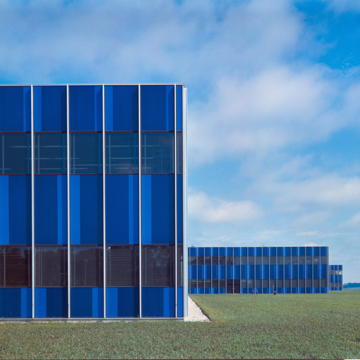

In Rochester, the buildings included one- and two-story volumes that sat in the middle of the vast site. Unlike other suburban corporate campuses that felt development pressures from the surrounding communities, IBM had an understanding with the City of Rochester to hold development back from the site, particularly between the building and the highway, to preserve the appearance of the campus in the landscape. The one-story volume located at the core of the facility houses the cafeteria and employee lounges. The other four, one-story volumes (250 x 250 feet) contain the manufacturing facilities. The four, 80 x 250-foot, two-story volumes contain the offices for the complex.

The nearly 100,000-square-foot building, then IBM’s largest facility, is based on a four-foot module that was developed for the curtain wall system. Saarinen and partner John Dinkeloo created this curtain wall using extruded aluminum mullions that held the two-toned blue porcelain enamel on aluminum panels, the largest panel being 4 x 8 feet. These panels were designed to be 5/16-inch thick, with a sheet of enameled aluminum on either side of a cement-asbestos core, the only element providing insulation on the entire building. These panels were then attached to the aluminum mullions with neoprene gaskets, the use of which Saarinen had pioneered at the General Motors Technical Center in Michigan. Horizontal division between the panels and the glazing were minimized, again, only using a neoprene gasket to seal the joint. The cost of the curtain wall system, according to the June 1957 issue of Progressive Architecture magazine, was only $4 per square foot of wall surface—this not only included the cost of the panels, but also the glass and the neoprene gasketing, all installed and completely finished on both exterior and interior faces. The striking blue color of this campus, some say, is the reason why IBM is informally referred to as “Big Blue,” but it also established an enduring brand, maybe by happenstance, for IBM. According to Thomas Misa, even though the origin of the color nickname remains a mystery, it is hard not to believe it references Saarinen’s assertively blue design, which, he suggested, was inspired by the Minnesota sky.

References

Harwood, John. The Interface: IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design 1945–1976. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011.

“In Rochester, Minnesota, IBM joins the community in preserving the rural surroundings of a new prestige plant.” Architectural Forum(October 1958): 140-143.

Misa, Thomas J. Digital State: The Story of Minnesota’s Computing Industry. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Pelkonen, Eeva-Liisa, and Donald Albrecht, ed. Eero Saarinen: Shaping the FutureNew Haven: Yale University Press, 2006.

“Saarinen Uses Curtain Wall 5/16” Thick.” Progressive Architecture(June 1957): 7.