The Minnesota State Capitol stands as an American monument of Renaissance Revival architecture. Designed and built between 1895 and 1905 as the state reached economic and political maturity, the Minnesota State Capitol has become over a century’s time the symbolic and functional heart of a wide-reaching civic complex. It also served as a springboard for Cass Gilbert, who began the project as an ambitious young St. Paul architect. By the time the capitol building opened on January 2, 1905, Gilbert was directing public and private commissions from his New York office.

The building is Minnesota’s third capitol, replacing a first lost to fire in 1881 and a second, designed by Leroy S. Buffington, that had become overcrowded as a new century approached. The Board of State Capitol Commissioners, led by Channing E. Seabury, selected a site to the north of and overlooking downtown St. Paul, with a view to the nearby Mississippi River Valley. Gilbert’s design was chosen by the commissioners after two competitions. He drew heavily on the template for American statehouses established by the United States Capitol in Washington, D.C. and other public buildings, particularly the Rhode Island State House commission recently awarded to McKim, Mead and White, in whose firm Gilbert had begun his career as a draftsman. Like other entries in the Minnesota competition, Gilbert’s proposal showed a classical composition with central entrance pavilion, dome, and statuary, but with a “severe simplicity” admired for the “symmetry of its proportions and the subordination of all ideas of ornamental detail to the general effect of the mass,” in the words of an editorial praising his selection.

Gilbert drew on the Italian Renaissance for inspiration, crowning the white marble facade with a dome based on that of St. Peter’s in Rome. At the foot of the dome, a gilded quadriga group, The Progress of the State by Daniel Chester French and Edward C. Potter, features four life-size horses pulling a golden chariot and guided by draped female figures; the charioteer holds symbols of Minnesota and its bounty. Six marble statues, also by French, represent civic virtues including Truth, Wisdom, and Courage. Citizens climbing the broad granite staircase could also find symbols of their state and nation amid the classical elements: five-pointed stars for “L’Etoile du Nord,” Minnesota’s motto; the stately initial “M” above deeply carved swags; and marble eagles around the drum of the dome.

The exterior stone was itself a matter of controversy and an early test of Gilbert’s political skills. Marble from Georgia, his stone of choice for its brilliant white color and classical associations, was not only expensive but sourced from a region that had been the site of Civil War battles for Minnesota soldiers who, now in their middle age, would regard the new capitol building as a monument to their sacrifices. Gilbert and Seabury secured a compromise for the costly “foreign” stone by using Minnesota granite and sandstone for the ground floor and terraces, and the Georgia marble—shipped in blocks and worked on site by Minnesotan laborers—for the upper stories and dome. The dome brought technical problems as well, which Gilbert solved by designing a supporting cone of brick and steel inside the marble structure to help withstand the extremes of Minnesota weather.

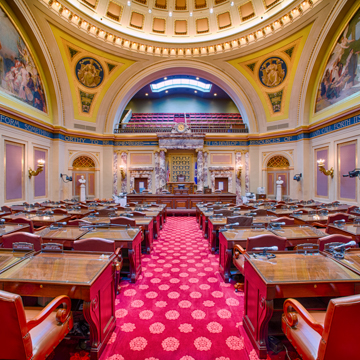

Inside, symmetry prevails in the floor plan and the circulation through broad hallways to the branches of state government. The rotunda rises some 142 feet from a star design set in the floor, past stone arches, to the painted and gilded inner dome. To the east and west of the rotunda, wide stone stairs rise beneath skylights and painted lunettes to the Supreme Court and Senate chambers. The governor’s suite occupies the west end of the first floor, while the House of Representatives, the state’s largest elected body, extends to the north on the second floor.

Gilbert and his chief decorator, Elmer E. Garnsey, again balanced aesthetics with politics to achieve sumptuous effects in the halls and chambers. They used Kasota and Mankato limestone for interior walls and Ortonville and St. Cloud granite for columns in the rotunda—all from Minnesota quarries—alongside richly figured columns and balustrades of imported Greek, Italian, and French marble. Gilbert and the commissioners negotiated budget increases to finish the interiors (lest they “be obliged to use ordinary wood work … and leave plain walls,” as a speaker warned at the cornerstone laying in 1898). Painted and stenciled decoration complemented stone walls and vaulted ceilings throughout the public spaces, crowned by a series of murals that brought Minnesotans a program of high art and classical ideals.

Gilbert and Garnsey marshaled the talents and experience of some of the country’s most prominent muralists: Edwin Howland Blashfield, Kenyon Cox, John La Farge, Edward E. Simmons, and Henry Oliver Walker. All were European-trained veterans of prestigious artistic campaigns like the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago and the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C. Their murals, painted on canvas in studios far from the Gopher State, allegorized history and law in the works of Simmons, Cox, and Walker in the rotunda and stair halls; dramatized the history of legal process in La Farge’s four Supreme Court compositions; and celebrated Minnesota’s history and aspirations in Blashfield’s huge Senate lunettes. Garnsey enlivened the House chamber with intricate patterns in color and gold that echo the state symbols on the facade.

Gilbert’s attention to detail extended to furnishings and fixtures. His drawings for sofas, armchairs, tables, and other essentials document near-obsessive efforts to create complete environments—a goal perhaps best appreciated in the semi-private spaces he designed and furnished for judges and legislators. His design for the Justices’ Consultation Room borrows colonial cues from Philadelphia’s Independence Hall, while the paneled and gilded Senate and House retiring rooms reflect Gilbert’s sketching tours of France and Italy. Toward the end of the capitol’s construction, Gilbert took advantage of public sentiment for Minnesota subjects (and a backlash against “dancing nymphs or goddesses on the walls of the Capitol,” as one Minnesota official and Civil War general put it) to shift his plan for the governor’s suite from “perfectly plain walls” to a scheme muralist and critic Kenyon Cox described as “conceived on the lines of a Venetian council chamber, with heavy, gilded moldings intended to frame historical pictures rather than decorations.”

The Governor’s Reception Room, completed shortly after the capitol opened, is one of the building’s most ornate public spaces—a showcase for Minnesota themes that still incite debate today. Dark oak and deep gold moldings enclose four paintings of Civil War battles in which Minnesota regiments played key roles, featuring portraits of some of their officers. Above the room’s two marble fireplaces hung large depictions of the 1680 “discovery” of St. Anthony Falls (in present-day Minneapolis), and an 1851 treaty signing that opened most of southern Minnesota territory by stripping the Dakota Indians of their land. While the paintings suited conceptions of history and heroism prevalent in 1905, some Minnesotans of recent decades have been critical of the subject matter and treatment. When the restored Reception Room reopened in 2017, those two paintings were removed for placement and interpretation elsewhere in the building.

The capitol opened in 1905 to popular acclaim in Minnesota and national interest in architectural circles. Cox and Garnsey wrote about it for The Architectural Record and Western Architect. Citizens who had debated the cost—which ultimately totaled $4.5 million—marveled at its grand spaces and mural decorations. But within a few years there were reports of overcrowding as state government and its departments grew. Gilbert had always conceived of his capitol as the centerpiece of a larger urban design, and in 1907 published a “Capitol Approach Plan,” which ordered the area, and the city around it, along broad radiating boulevards typical of the City Beautiful movement. He maintained an interest in this until the end of his life, even as new state buildings were constructed around sweeping lawns before the capitol building. While none of the subsequent state buildings approach the capitol in grandeur of scale or design, the outlines of Gilbert’s vision still guide what has grown to be a large civic complex.

Time, weather, and politics were hard on the capitol throughout the twentieth century. Daily use for state business brought wear and tear, while demonstrations like a Depression-era occupation of the Senate chamber by populist protesters strained the fabric of the building. A large spectators’ gallery in the House chamber was walled off to conceal new office space behind a sculpture group added in 1938. Successive remodelings altered color schemes and furnishings, rarely for the better. State offices crowded the building to the extent that plywood partitions lined some hallways in the 1970s. Meanwhile the capitol area expanded with new buildings in postwar styles for the revenue, transportation, and veterans departments. The legislature created the Capitol Area Architectural Planning Board in 1967 to guide development of the complex and, together with the Minnesota Historical Society, oversee preservation of the capitol at its center.

Maintenance and restoration projects kept the basic form and features of Gilbert’s design intact through its first century. Restoration efforts began as early as the 1930s to 1950s, a time when the capitol was considered, in the words of art historian Donald R. Torbert, “elaborate, expensive—and impractical.” By the 1980s a renewed interest in classicism and preservation helped Minnesotans appreciate their aging statehouse and, through their legislators, fund restoration projects for the Senate chamber, the quadriga, and selected murals, as well as roof repairs and landscaping. The building closed for wholesale restoration from 2014 to 2017, which included replacement of hundreds of pieces of marble with stone from the original Georgia quarry, repair of plaster walls, cleaning of murals and decorative paintings, and uncovering the skylights.

The work also included reconfiguring many spaces for new public uses, as well as the introduction of twenty-first-century data infrastructure. Just as in the capitol’s original design period, the voices of the people continue to be heard, sometimes in heated discussion, as Minnesotans debate the values and messages embodied in their capitol building—especially the absence of women and people of color, and the reevaluation of men once lionized as the state’s founders. While the coming years may see the removal of some period artworks and the addition of new pieces reflecting more diverse viewpoints, Cass Gilbert’s vision remains alive and refreshed as a touchstone of Minnesota civic life.

References

Christen, Barbara S. and Steven Flanders: Cass Gilbert, Life and Work: Architect of the Public Domain. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2001.

Gardner, Denis P. Our Minnesota State Capitol: From Groundbreaking through Restoration. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2017.

Irish, Sharon: Cass Gilbert, Architect: Modern Traditionalist. New York: Monacelli Press, 1999.

O’Sullivan, Thomas North Star Statehouse: An Armchair Guide to the Minnesota State Capitol. St. Paul: Pogo Press, 1994.

Thompson, Neil B. Minnesota’s State Capitol: The Art and Politics of a Public Building. St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 1974.