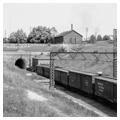

The St. Clair Tunnel was the first international submarine railway tunnel in the world. It is 6,025 feet long and with its approaches reaches 11,553 feet. It cost nearly $3 million to construct. At the urging of Henry Tyler, president of the Grand Trunk Railway, the directors of the Grand Trunk organized the St. Clair Tunnel Company in 1886 to build a tunnel between Port Huron and Sarnia. The Grand Trunk had been completed to Chicago six years earlier, and ferries had carried railroad cars across the swiftly moving, frequently ice-jammed, and heavily navigated river. The location of the tunnel was determined by the comparatively low depth of water at the crossing, the ability to construct the tunnel and its approaches on the same straight line, the short length of new railway that would be required, and the favorable material in the bed of the river for tunneling.

Joseph Hobson of Guelph, Ontario, designed and built the tunnel. To accomplish this he constructed, set in place, and successfully operated two gigantic tunneling shields based on the tunneling method invented by Alfred E. Beach of New York City and patented in 1868. Made of one-inch-thick plate steel, the shields were twenty-one feet seven inches in diameter and sixteen feet long. Twenty-four hydraulic rams located around the rear of the shield forced the sharpened leading edge of the shield into the clay. Tunnelers in the front of the shield removed and carried back the soil through the shield. An air pressure system aided in holding up the soft earth of the tunnel heading. As the shield progressed, the iron tube was constructed. The tunnel's walls are composed of segmental flanged iron plates connected by bolts. One ring is composed of thirteen of these iron plates and a key. The lower half is lined with brickwork. The round-arched portals of the tunnel are set within rusticated limestone walls surrounded by voussoirs, and over them is a small pediment containing the inscription “Saint Clair, 1890.” Westinghouse Company installed electricity to haul the trains in 1907, making the tunnel well lighted, clean, and safer. “The Old Bore,” as the tunnel is called, is no longer used for trains and provides maintenance access to the new tunnel and a conduit for pipes to pump out water seepage and runoff from the approach grades.